Catholic Social Teaching, waning Anglicanism, and the antidote to purposeless secular education | Tom Colsy

What have been the biggest hindrances to the continuation of Christian faith and morality? In Europe over the years, two institutions have historically taken on the responsibility of passing on such values and belief systems: the family and the education sector.

The depressing truth is that emerging reports claim that under 2% of children in the United Kingdom now identify as Anglicans. The very religion of state- that has dominated for close to two millennia – risks becoming an outright minority and fringe in its own country. And to put it bluntly, this is not because children have begun looking to the Vatican in Rome. Yet, despite their newfound ‘liberating’ irreligiosity, they are suffering. They aren’t looking to Rome, but perhaps they should be.

Of the two vital aforementioned societally-foundational institutions, the former is today, unfortunately, mortally wounded. In the 21st century, the family model is more unstable, weak and disposable than ever before. Britain’s rates of fatherlessness are currently at record highs, a trend there seems to be little political will to tackle, even among conservatives. It is critical, therefore, that the second institution does not neglect, nor forget, its long-held responsibilities.

The greatest failure that prior generations have gifted the newer lies not in the housing crisis, nor the state of the economy, but in raising children in a manner in which all purpose and spirit is stripped out of the human condition (what do we teach children the greater goal of their attendance in school is? The acquisition of material things, of course). The secular, bland, uninspired, vacuous and ever so vague-in-purpose education we begrudgingly hand onto them is not only harmful to the very fabric of our society but is a cruelty in itself- and has a human cost.

And as if to prove that there exists a crisis in our education system, our schoolchildren in Britain are some of the most atheistic – yet they are also shockingly the least likely in the world to agree with the statement “my life has clear meaning or purpose”. Simultaneously, and of course completely coincidentally, statistics are underlining that British youth depression and mental illness are on the rise. Unrelated, I’m sure. Nihilism has always been the great vitality of life.

In education, the interests of accommodation have taken precedence over the spiritual and moral development of our children, and we have lost belief in ourselves. Meanwhile, the social cost of leading our children to nowhere has been proliferating.

But when asking questions of how to halt Christianity’s unceasing decline in our hedonistic consumer culture, and of how to prevent the trend of children abandoning spirituality to their own detriment, it’s not outrageously daring nor audacious to suggest that revisiting our approach to education might just be a logical place to start.

So, where could the solution to such a destructive pandemic of relativism and lack of direction lie? As is so often the case, the antidote can be found by looking to the wisdom of the past.

The photo heading this article is of Château de Bonnelles on the outskirts of Paris, near the district of Versailles. It is where my father was educated. In the early 1960s the members of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, provided him rigorous theological teachings that would raise many eyebrows in secular modern-day Britain.

Recently, standardisation has been the order of the day in the education sector; variety has been the enemy. With an ever more religiously diverse population, the tradition of passing down Christian values, at least in the overt sense, is one that has gradually withered in our institutions and schools. And this means we have also lost the wisdom that comes with it.

This was never the case for the children of Yesterday. For all the modernism to his project, and his former revolutionary Trotskyism (as Peter Hitchens likes to remind us), a surprisingly significant legacy of Tony Blair’s premiership was his project of faith schools, one which attained him much criticism on the political left. But a recent study has evidenced that it is a good legacy. Certain types of faith schools yield results; Christian schools in the UK perform ‘consistently well’ in English, while Roman Catholic and Church of England schools ‘perform above the norm’ on certain outcomes. Evidently there is merit in the unification of the spiritual and the intellectual advancement in the student’s wider educational experience.

Now, where some may imagine the Jesuit education to have been dogmatic and one of sinister indoctrination, it might surprise readers that ambiguity is a concept that students educated by Jesuits would testify to be recurrent during their upbringing. Students were told to embrace it, to reflect upon it deeply and to use it to pursue truth. This is something that especially differentiates Jesuit education from its lacklustre contemporaries.

My father recalls a memory of passing by a priest in the halls of his school and being stopped. “Which studies have you attended today?” he was asked, before being left desperately confused by the priest’s instruction to think about the philosophical links between what he had learned in his German language and Science classes earlier that morning.

I posit; how often in British education are children asked to do anything more than merely unthinkingly consume and regurgitate what is in front of them, let alone perform such a daunting task as to seek higher meaning among it?

As teenagers on the streets of London and Birmingham hack each other to pieces with machetes and knives (a trend that has seen a 93% increase in the last five years), it is clear the secular humanist instruction to ‘respect one another’ for utilitarian ends has not proven adequate. Catholic Social Teaching would neither go amiss. It calls for:

Life and Dignity of the Human Person.

Family, Community, and Participation.

Rights and Responsibilities.

Option for the Poor and Vulnerable.

The Dignity of Work and the Rights of Workers.

Solidarity.

Care for God's Creation.

The Jesuits go a step further than handing a list of social instructions. They attempt to complete the individual and make him whole, so that he is at peace with himself and his goals are clear, and so he can proceed to live for others. An important mission. This means unifying his thoughts, discovering his values and articulating them into a cohesive self. Unity of Heart, Mind, and Soul is one of six Jesuit values in education. In this sense, their teaching serves as the ultimate foil to relativism. Every student is instilled with a strong mission for their presence on Earth by the Jesuits, with vitality and veracity, according to the mandate given to mankind by Christ.

Many accusations can be slung around about the schooling – theological, strict, militaristic – but purposeless it is not. And perhaps this is where the antidote lies. In re-attaining a mission of purpose within schooling.

The other noble principles that feature in the Jesuit approach to education are:

Cura Personalis (care for the individual person – respecting each person as a child of God and all of God’s creations),

Magis (literally translated as ‘more’ – the promotion of the challenge to strive for excellence),

Women and Men for and with Others (a spirit of giving and providing service to those in need and standing with the poor and marginalized, encouraging to pursue justice on behalf of all persons),

Contemplatives in Action (while remaining thoughtful and philosophical, not merely thinking about social problems but taking action to address them. As developing the habit of reflection centres and strengthens one's spiritual life, and guides our actions).

The final of those listed above is obviously a concept we could all do a bit more to honour. Highlighting issues in society is a frivolous action anyone can perform. Doing something about it thereafter, is where most falter.

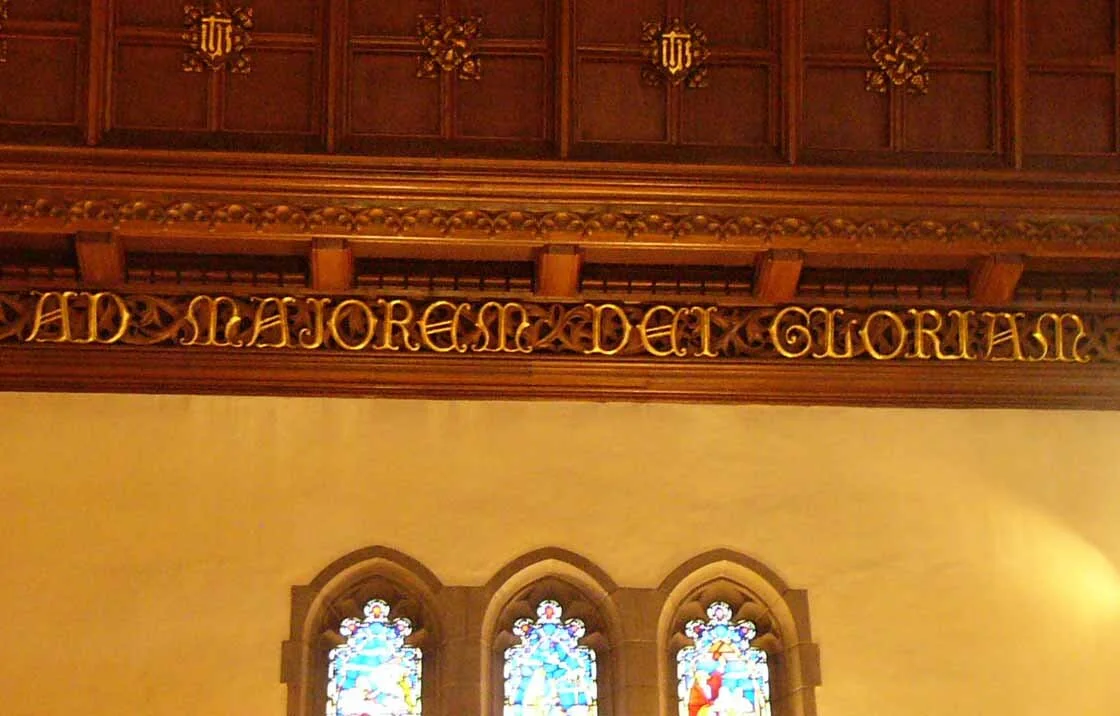

The last and most powerful is the principle of Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam – literally translated as ‘for the greater glory of God’. A Romano-Christian ‘SPQR’ if ever there was one. AMDG entails both living with intent of serving divinity in gratitude and aspiration, but also to find God in all things. The expression represents Ignatian Spirituality well. It invites the individual to search for and find God in every circumstance of life; God is present everywhere and can be found in all creation.

This attitude combats a fallacy strangely allowed to purvey among youth. Here, Catholic students were taught not to see the world, the universe and human life in all its scientific detail, light and darkness as somehow contra or foil to faith- but to embrace it. To pursue it with openness and curiosity. Doing this alongside a lasting and deep gratitude for the gift of life. This, sadly, is not the case for British schools, nor for British children.

My father went on to become a pilot, later a captain, and his success was far from atypical of those who graduated from his dear school with those among his friends becoming lawyers, architects, high profile journalists, businessmen and writers. To many in his life, he is a collected and complete human being that offers consolation, strength and humility to those around him. This is something integral to his character that seems inbuilt – never strained nor forced. To me, that is a testament to the Jesuits. Perhaps we could continue that legacy.